β-Elimination Reactions

In organic chemistry class, one learns that elimination reactions involve the cleavage of a σ bond and formation of a π bond. A nucleophilic pair of electrons (either from another bond or a lone pair) heads into a new π bond as a leaving group departs. This process is called β-elimination because the bond β to the nucleophilic pair of electrons breaks. Transition metal complexes can participate in their own version of β-elimination, and metal alkyl complexes famously do so. Almost by definition, metal alkyls contain a nucleophilic bond—the M–C bond! This bond can be so polarized toward carbon, in fact, that it can promote the elimination of some of the world’s worst leaving groups, like –H and –CH3. Unlike the organic case, however, the leaving group is not lost completely in organometallic β-eliminations. As the metal donates electrons, it receives electrons from the departing leaving group. When the reaction is complete, the metal has picked up a new π-bound ligand and exchanged one X-type ligand for another.

Comparing organic and organometallic β-eliminations. A nucleophilic bond or lone pair promotes loss or migration of a leaving group.

In this post, we’ll flesh out the mechanism of β-elimination reactions by looking at the conditions required for their occurrence and their reactivity trends. Many of the trends associated with β-eliminations are the opposite of analogous trends in 1,2-insertion reactions. A future post will address other types of elimination reactions.

β-Hydride Elimination

The most famous and ubiquitous type of β-elimination is β-hydride elimination, which involves the formation of a π bond and an M–H bond. Metal alkyls that contain β-hydrogens experience rapid elimination of these hydrogens, provided a few other conditions are met. Read the rest of this entry »

Migratory Insertion: 1,2-Insertions

Insertions of π systems into M-X bonds are appealing in the sense that they establish two new σ bonds in one step, in a stereocontrolled manner. As we saw in the last post, however, we should take care to distinguish these fully intramolecular migratory insertions from intermolecular attack of a nucleophile or electrophile on a coordinated π-system ligand. The reverse reaction of migratory insertion, β-elimination, is not the same as the reverse of nucleophilic or electrophilic attack on a coordinated π system.

Like 1,1-insertions, 1,2-insertions generate a vacant site on the metal, which is usually filled by external ligand. For unsymmetrical alkenes, it’s important to think about site selectivity: which atom of the alkene will end up bound to metal, and which to the other ligand? To make predictions about site selectivity we can appeal to the classic picture of the M–X bond as M+X–. Asymmetric, polarized π ligands contain one atom with excess partial charge; this atom hooks up with the complementary atom in the M–R bond during insertion. Resonance is our best friend here!

A nice study by Yu and Spencer illustrates these effects in homogeneous palladium- and rhodium-catalyzed hydrogenation reactions. Unactivated alkenes generally exhibit lower site selectivity than activated ones, although steric differences between the two ends of the double bond can promote selectivity. Read the rest of this entry »

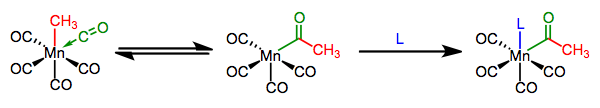

Migratory Insertion: Introduction & CO Insertions

We’ve seen that the metal-ligand bond is generally polarized toward the ligand, making it nucleophilic. When a nucleophilic, X-type ligand is positioned cis to an unsaturated ligand in an organometallic complex, an interesting process that looks a bit like nucleophilic addition can occur.

On the whole, the unsaturated ligand appears to insert itself into the M–X bond; hence, the process is called migratory insertion. An open coordination site shows up in the complex, and is typically filled by an added ligand. The open site may appear where the unsaturated ligand was or where the X-type ligand was, depending on which group actually moved (see below). There is no change in oxidation state at the metal (unless the ligand is an alkylidene/alkylidyne), but the total electron count of the complex decreases by two during the actual insertion event—notice in the above example that the complex goes from 18 to 16 total electrons after insertion. A dative ligand comes in to fill that empty coordination site, but stay flexible here: L could be a totally different ligand or a Lewis base in the X-type ligand. L can even be the carbonyl oxygen itself!

We can distinguish between two types of insertions, which differ in the number of atoms in the unsaturated ligand involved in the step. Insertions of CO, carbenes, and other η1 unsaturated ligands are called 1,1-insertions because the X-type ligand moves from its current location on the metal to one spot over, on the atom bound to the metal. η2 ligands like alkenes and alkynes can also participate in migratory insertion; these reactions are called 1,2-insertions because the X-type ligand slides two atoms over, from the metal to the distal atom of the unsaturated ligand.

1,2-insertion of an alkene and hydride. In some cases, an agostic interaction has been observed in the unsaturated intermediate.

This is really starting to look like the addition of M and X across a π bond! However, we should take care to distinguish this completely intramolecular process from the attack of a nucleophile or electrophile on a coordinated π system, which is a different beast altogether. Confusingly, chemists often jumble up all of these processes using words like “hydrometalation,” “carbometalation,” “aminometalation,” etc. Another case of big words being used to obscure ignorance! We’ll look at nucleophilic and electrophilic attack on coordinated ligands in separate posts.

Reductive Elimination: General Ideas

Reductive elimination is the microscopic reverse of oxidative addition. It is literally oxidative addition run in reverse—oxidative addition backwards in time! My favorite analogy for microscopic reversibility is the video game Braid, in which “resurrection is the microscopic reverse of death.” The player can reverse time to “undo” death; viewed from the forward direction, “undoing death” is better called “resurrection.” Chemically, reductive elimination and oxidative addition share the same reaction coordinate. The only difference between their reaction coordinate diagrams relates to what we call “reactants” and “products.” Thus, their mechanisms depend on one another, and trends in the speed and extent of oxidative additions correspond to opposite trends in reductive eliminations. In this post, we’ll address reductive elimination in a general sense, as we did for oxidative addition in a previous post.

A general reductive elimination. The oxidation state of the metal decreases by two units, and open coordination sites become available.

During reductive elimination, the electrons in the M–X bond head toward ligand Y, and the electrons in M–Y head to the metal. The eliminating ligands are always X-type! On the whole, the oxidation state of the metal decreases by two units, two new open coordination sites become available, and an X–Y bond forms. What does the change in oxidation state suggest about changes in electron density at the metal? As suggested by the name “reductive,” the metal gains electrons. The ligands lose electrons as the new X–Y bond cannot possibly be polarized to both X and Y, as the original M–X and M–Y bonds were. Using these ideas, you may already be thinking about reactivity trends in reductive elimination…hold that thought. Read the rest of this entry »

Oxidative Addition of Polar Reagents

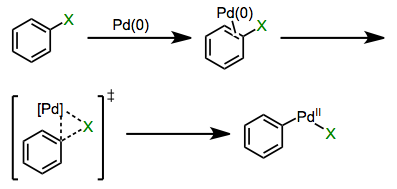

Organometallic chemistry has vastly expanded the practicing organic chemist’s notion of what makes a good nucleophile or electrophile. Pre-cross-coupling, for example, using unactivated aryl halides as electrophiles was largely a pipe dream (or possible only under certain specific circumstances). Enter the oxidative addition of polarized bonds: all of a sudden, compounds like bromobenzene started looking a lot more attractive as starting materials. Cross-coupling reactions involving sp2– and sp-hybridized C–X bonds beautifully complement the “classical” substitution reactions at sp3 electrophilic carbons. Oxidative addition of the C–X bond is the step that kicks off the magic of these methods. In this post, we’ll explore the mechanisms and favorability trends of oxidative additions of polar reagents. The landscape of mechanistic possibilities for polarized bonds is much more rich than in the non-polar case—concerted, ionic, and radical mechanisms have all been observed.

Concerted Mechanisms

Oxidative additions of aryl and alkenyl Csp2–X bonds, where X is a halogen or sulfonate, proceed through concerted mechanisms analogous to oxidative additions of dihydrogen. Reactions of N–H and O–H bonds in amines, alcohols, and water also appear to be concerted. A π complex involving η2-coordination is an intermediate in the mechanism of insertion into aryl halides at least, and probably vinyl halides too. As two open coordination sites are necessary for concerted oxidative addition, loss of a ligand from a saturated metal complex commonly precedes the actual oxidative addition event.